An hermitage, or almost. A miniature village perched on a limestone cliff, a medieval gem now almost depopulated. It’s an autumn day, with a tramontana wind and sharp outlines sketching the profiles of the Albegna and Fiora Hills all around, at the foot of Monte Amiata. In winter, without the owners of second homes, there are 24 inhabitants in Rocchette di Fazio, two of them children who, at least, have the good fortune to grow up surrounded by breathtaking landscapes and steeped in a history rooted in the High Middle Ages. And then there is her, Agata Felluga, the Dame en blanc of Rocchette di Fazio, the lady of the Cacciaconti fiefdom with her trattoria that inhabits the square rightfully named after her: “Could I have found a more appropriate name? The name, that of Fazio Cacciaconti from the Aldobrandeschi family, evokes ancient disputes.”

Now there is only one dispute left: keeping the village alive.

The day calls for a walk through the woods and scrub, an inevitable complement to Agata’s cuisine: “See that field? It was dad’s favorite spot for our snacks, and that memory brought me back to Rocchette.” Heroic hospitality, to be cultivated in the middle of nowhere, in total isolation. But her trattoria, we are certain, is a good fuel to revive the districts. Because Agata, by nature and training, is one of those people who are naturally inclined to network, to spark curiosity, to share, to seek out like-minded individuals. And fortunately, similar souls are not lacking within a radius of several kilometers, and we will see that.

First, let’s try to understand who this stunning forty-year-old woman is, who seems to have stepped out of a French film, with her long braid framing an ancient yet modern face in an unfathomable mix of rigor and lightness, that charm you would love to steal from French girls. If you sit in a Parisian café, you would see dozens of them passing by with that unmistakable style. Yet, Agata is not French. She is Italian, very Italian, and here we are not in Paris even though French is spoken in the kitchen with the sous chef, but above all with her friend Léa, with the music perpetually tuned to the radio channel France Musique and the canonical interjection, very French, oh là là.

Léa, with a hairstyle that seems to come straight out of the illustrator Charles Dana Gibson’s pen with the volume of her hair cascading down the front of her face, is Agata’s indispensable partner: “without her, I could never make it.” The Gibson girls: ironic women, the right kind, in pristine chef uniforms with navy blue aprons (hard to find in Italy), blue like the sea filtering in the background (“My parents settled in Rocchette because beyond the hills, they could catch a glimpse of Giglio Island”), navy-striped shirts, Breton stripes, of course, during moments of uniform downtime. Agata wears her apron only when she’s in the kitchen; when she goes out to the dining room, in the heroic back and forth, the uniform is strictly white illuminated by a bold red lipstick signifying confidence and audacity. She doesn’t appreciate customers who take the liberty of addressing her informally at first sight; trust must be earned.

So, who is Agata and what is she doing in the splendid isolation of Rocchette di Fazio?

She has a long and unbreakable bond with the village. Thanks to two enlightened parents, both biologists and researchers at the National Research Council of Rome, who would never skip a weekend to escape the Capital and bring their two daughters to the tranquility of this corner of Maremma, not far from the Terme di Saturnia. A cultural and family background of international influence: mom Sandra was born in Shanghai where she lived with her parents, Agata’s grandmother is from Trieste, and her grandfather is German. “A friend of my mom, Russian and also from Shanghai, an amazing cook, introduced me to this world.” On the other hand, her father, Papà Bruno, from Istria, is a passionate follower of macrobiotics and an unwavering experimenter in the field. All of this leaves a trace of Central European and beyond customs and partially explains Agata’s choice. As Freud wrote, “The past acts in the shadows.”

The parents, who have long settled permanently in Rocchette, were the inspirers of the daughter’s return, two years ago, from distant worlds. “Look, the trattoria is for sale, if you’re interested, send a signal right away.” The signal came suddenly, without delay. At this point, the mother still cannot believe it: “I have always wanted my daughters to be free and move away from home. Now, incredibly, they have returned.” Rewinding the crumbs of the path backwards, one fully understands the reasons behind it. Agata explains that her taste was formed primarily as a customer, trying out dishes at restaurants where she would stop with her family on weekends. “Traveling along the Cassia, every time we would stop at one of the many inns scattered along the road, some amazing ones.” She says this while sipping a cup of tea that always keeps her company: “I couldn’t live without it. I also use it as broth or for deglazing. I didn’t learn it from anywhere, I just like it.”

But the special memory is for the tortelli di Corinto at the homonymous locanda (trad. inn) in San Martino sul Fiora, her childhood dish. Many fear now that him and his wife, both over eighty, may leave and “it would be a tragedy. His tortelli are still a paradigm for me. Like Franca’s aquacotta (the neighbor, ed): they are perfect dishes. I decided to return precisely because I had their cuisine in mind.” Agata’s idea is indeed to build a network of restaurateurs who are committed to preserving a heritage of local recipes because, once the actors who hold the small details disappear, the memory of those flavors will fade. Another experience, always as a customer, marked her, but this time of a different nature: “At the Plaza Athénée by Ducasse I said to myself: wow, oh là là! This is how it’s done.””

Her tour through the kitchens of Michelin-starred restaurants would later chart her path, taking her from dishwasher (yes, indeed, this is part of every young emigrant’s CV) to chef de partie (“but I must set the record straight once and for all: I was never a sous chef”), in the indispensable maisons of a proper gastronomic education. After completing her classical studies at one of Rome’s finest high schools, she followed her passion for the arts with eclectic studies at the DAMS in art, screenwriting, and directing. But the plot of her own script would soon be written through her zigzagging across various temples of French gastronomy: a stint in 2005 at Alain Senderens in Paris, then at Pascal Barbot’s L’Astrance, and subsequently at Le Chateaubriand with Iñaki Aizpitarte. It was Barbot himself who suggested she make the move to Iñaki:

“You are an artist, he used to repeat to me, meaning by this that I was somewhat unreliable. A double-edged sword as from an artist you can expect anything. He often asked me what I wanted to do when I grew up because, he said, a chef needs to know: what will you do now with my legacy? If I look back at that period, it all seems very far away.”

Following four years at Le Chateaubriand, “The place where I had the most fun ever. I spent the first six months laughing so much, I hadn’t laughed like that in years. Everything was improvised, the recipes didn’t exist, nor were they reproducible, not even Iñaki would know how to make them. The crucial turning point was indeed discovering that I could have fun in the kitchen. We were so happy cooking with Iñaki; this crazy chef who showed me the possibility of total freedom in the kitchen. Just have the ingredient and olé! The fundamental lesson from those years is that, in addition to the quality of what you have on the plate, the atmosphere around you is also important. And the atmosphere at Le Chateaubriand was truly incomparable. But it’s a past that I have left behind, I have done many other things and I don’t want to remain chained to those experiences.”

Sometimes in the script of life, one ends up where they shouldn’t be.

And so the unease and a “gone sour” love story lead her to Strasbourg in a completely different context, the punk rock world, in an underground realm of encrypted codes. “I have always felt like a stranger in France, and for the umpteenth time, I started with a clean slate.” The new scene she immersed herself in is the Franco-German underground cultural scene where she formed very close relationships with artists who brought to life a culture of art, creative collectivity, and rebellious energy translated into experimental music, flyers, fanzines, posters, and much more. “A very peculiar break, a way to distance myself from what had come before.” There, Agata learned to set up stage designs, create silkscreens, design posters for music groups, started organizing concerts, events, and above all, cooking for this large community. Thanks to the team at Collectif Sin in Dordogne, she met Léa, who would later follow her to Rocchette. “Without the help of friends, I would have never opened the trattoria.” Blacksmiths, artists, artisans. “I hosted them, and they all lent a hand. A blacksmith friend handmade the sign for the establishment.”

In Strasbourg, she also cultivates her musical passion. Through the Grande Triple Alliance Internationale de l’Est – whose symbol is the modified Cross of Lorraine – she connects with an artistic and contemporary music collective whose members identify esoterically with the symbol. “A spontaneous collective that marks a sense of belonging, with people playing under bridges, wherever there was a free space. You would see the cross drawn on the door of a bathroom, and that’s when you knew something musical was happening. There’s a private YouTube documentary that tells this underground world well.” Exploring the current cellar of the trattoria, walls steeped in centuries of history, reignites the feelings of the documentary showcasing underground spaces used by musical groups, but here, the drums are made of jars of various kinds: oignons pickles, citron confit, coing (quince), jams, jellies… and bundles of wood for the oven, hanging salamis (produced by Agata), and wine, lots and lots of wine. “We need to preserve because in Rocchette di Fazio, there isn’t the availability of ingredients found in big cities.”

The flow of old and new friends arriving from across the Alps continues uninterrupted, even though the girl dressed perpetually in black as any respectable punk has made way for the Dame en blanc. “Now it’s a pleasure to finally dress all in white.” However, she remains intimidated and perplexed by the many arrivals and especially by the unexpected hustle and bustle among industry professionals: “But at this moment, I would just like to be able to focus on my cooking without generating too many expectations. I fear that people, after undertaking this journey outside the world, will be disappointed.” She says she has broken ties with the gastronomic star system, leaving it behind and desiring only to be able to do her job in total simplicity and freedom.

“I don’t follow laws written in blood, I simply avoid catapulting myself back into a system that no longer belongs to me. Unfortunately, I have the feeling that many customers expect a gourmet restaurant, I see it, I feel it, but that’s not what I have in mind. Mine is meant to be a cuisine liberated from the need to conform and from expectations. Yet, I spend my time wondering, asking customers if everything is okay, if they are well, even asking the refrigerators, and Léa replies to me, ‘Yes, the refrigerators say hello to you.’ Even though I cook in Italy, Agata doesn’t see herself as an Italian cook. ‘I like to play with the codes of gourmet cuisine, it’s my niche, but without constraints.’ She loves those hiking customers (and the trails of Semproniano and the WWF Oasis natural reserves are a real paradise for trekking) who walk miles arriving famished at the Trattoria, ready to continue their journey once they’ve eaten. ‘They are my ideal customers.’”

The essence of Michelin-starred cooking is indeed everywhere, a wealth of nuggets fully internalised.

“And those who cannot grasp these gems perhaps do not deserve Agata. ‘Two of the things I learned from Pascal (Barbot) are the interpretation and the psychology of the ingredient, they come before everything else, you have to proceed in reverse, à rebours, the gestuality, the respect, like touching the leaves of a salad and this goes beyond technique and nobody ever teaches you this. Between two salad leaves, there will always be one that you will be more eager to serve.”

She says while caressing le coeur de la salade that she will then dress in orange juice.

Agata just wants to continue the tradition of good things that once dotted this territory, things made with art and heart that modern times are sweeping away, a recovery of simplicity just garnished with what modernity has taught but as a pure background, an underlying plot that should not be seen, concealed, hidden. “Mine is the unlearning process, abandoning what kept me caged. Moving to this place has meant for me a thorough introspection. I’ve never learned so many things in such a short time and at such an intense voltage. Without therapy, I started to understand what I couldn’t grasp before. From all the positive feedback I’ve received, at this point, I should stop doubting myself. I am as you see me and as what you taste.”

Not surprisingly, the technique she is most fond of is making fresh pasta: “It’s sexy beyond borders, it’s a date, a romantic encounter.” All her recipes are seemingly simple, but what makes them special is the touch, the experience. “Even to make pasta, a touch is needed, it’s right there where you feel like everything can change,” like with Pici, for example: ancient grain flour, salt, a drizzle of oil, and boiling water “but you have to work them little due to the dough’s tendency to dry out, crack, you have to feel them, subdue them.” It’s all a matter of sensitivity, which you can feel in Maltagliati greens, ravaggiolo, and hazelnuts; in Tagliolini with chickpeas and rosemary; in Tagliatelle with ragu; in Black Tagliolini with bottarga. Or in Pappardelle dressed with green sauce made with almond flour and parsley. Completing the script of Maremman first courses are Gnudi with chard and pastorino; Gnocchi with butter and sage; the incomparable Acquacotta which has all the intensity of celery and a recipe that comes from the past.

“At first, I wanted to do vegan cuisine then I changed my mind. It seems that in this world, you can’t do without meat. The technique for cooking meats, especially poultry, is all from Barbot’s playbook, strictly done on the bone.”

The meat, what meat!

Agata’s meat comes from the Tenuta Aia della Colonna, spanning 240 hectares in Roccalbegna between Mount Amiata and the Argentario Coast. Agata has a long-standing relationship with the Tistarelli family from her childhood. Their farm is a true agriturismo (what better definition?) that combines heroic farming with an equally heroic dining experience. In this case as well, everything is based on word of mouth, rather than on signage, challenging those who navigate the winding and difficult roads to wonder if it was truly worth it in the end. Oh, but it is worth it. Observing the Maremman cattle grazing as if in a Macchiaioli painting is an experience. Then there are the incredible cold cuts, from fennel salami to “cinta” pork salami, pancetta, prosciutto, aged sausage, lard… The Cinta Senese pigs live freely in the vast spaces of the estate. Agata’s Pork Shoulder with Pancetta dish is derived from this prime material and shines with many invisible micro-techniques: wrapped in fig leaves, it undergoes a long and slow cooking process, but not vacuum-sealed. The accompanying pancetta is cooked for half a day in a mixture of milk and tea with juniper and bay leaves, then cooled in its liquid. The two parts, shoulder and pancetta, are then brought together with a touch of jus de viande, black olive powder, and choucroute.

“Yes, a lot of little eye winks, not for nothing I was in Alsace for a long time and my potatoes are cooked in lard by necessity.” On the pass, all the powders are lined up, her flavor gems: verbena, citrus, za’atar, sumac, dukkah… “Today, powders are often a shortcut with pairings lacking structure, there’s a freedom without rigor, but they need to be interpreted.” Barbot’s teaching regarding spices is still indelible. The myrtle powder sprinkled on the slices of Salami is, for example, an unexpected touch that ignites curiosity and appetite. The helichrysum powder on pecorino and pears is the same. The Cecina and chickpea hummus sprinkled with cumin, za’atar, and sumac is a Middle Eastern plunge. Everything flows with simplicity at the trattoria: the tagliata, which in these parts is a sort of creed, is still more profound with Aia della Colonna meat. Likewise with the classic Peposo. A true transgression is the Chicken cutlet with frites, which is a huge hit (not surprisingly). Her Baccalà with polenta is consecrated by intense laurel flavors. The herbs of the scrub are a sort of epilogue to many dishes, like the powders and rightly so in desserts. As in the Honey gelato with “tozzetti” and fig leaf powder.

The Grape-Strawberry Sorbet with strawberry gelée and dried and chopped grapes draws from the provisions of the cellar. Agata’s ice creams are made without stabilizers or additives. Her herbal liqueur is a blend of all available essences: helichrysum, lavender, thyme, laurel, lemon verbena, basil, mint, rosemary… After all, look at the landscape and the landscape enters your plate.

“The thing to really learn is to enter the kitchen with peace of mind. If I am calm, the team is calm.”

The truth squad is extremely short-staffed.

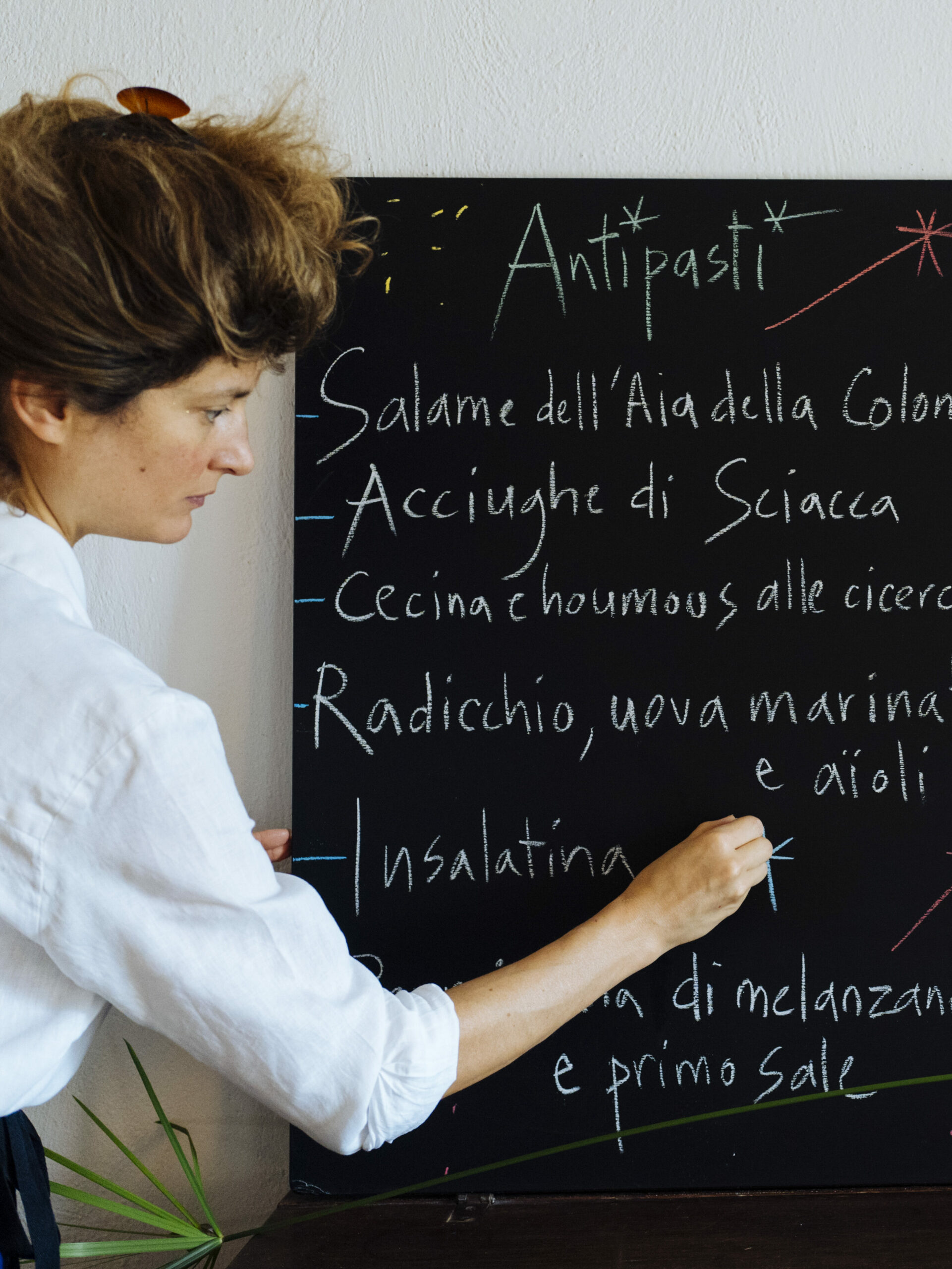

At the time of our visit, there are precisely two people in the kitchen, her and Léa. “Here, we all do everything, wash the dishes, clean the floors, and design the seasonal menu, then write it on chalkboards.” The instruction to customers is to take a picture of the menu on the chalkboard, no QR code, “but even this already disrupts things. Desserts? You get up and read the chalkboard.”

In the kitchen, classical music accompanies every moment of the day, and to understand Agata’s love for music, inherited from her parents and cultivated everywhere, including the Strasburg bands, one only needs to step into her private apartment above the restaurant (a privilege we had) with walls lined with vinyl collections gathered from across time and space, with a particular fondness for Miles Davis. From the kitchen, the music radiates into the dining room. “I noticed the power of sounds coming out of the kitchen, Schubert always works when you want the customers to leave. And all the recipes have a liaison with music, they are refrains, childhood stories, ‘this is the harmony I seek.’ Meeting Léa in the music scene, music is probably the strong bond of their friendship.”

Léa, who studied singing at the Conservatory and Industrial Creation at the École Nationale Supérieure in Paris, also completed a transatlantic journey on a sailboat: “Cooking on board c’est geniale, the kitchen is like a galley.” In fact, amidst pots and jars, the order is meticulous, as it should be, given that the spaces are that of a galley.

The adventure of Agata and Léa also involves wines.

It was at Astrance that Agata focused her passion for natural wines thanks to the legendary sommelier Alexandre Jean (first met through Senderens). “I didn’t know much about natural wines, but I suffered from terrible migraines and realized I could drink them without any issues. It was like a Eureka moment, an epiphany: the true taste of wine, unfiltered… Sulfites seemed like insurmountable obstacles to me when trying conventional wines; I felt like I had to search for the vine’s fragrance and aroma with a torch, often without success.” Alexandre Jean created surprising alchemies with Barbot. Pascal adjusted the dishes based on the wine choice made by the customer following Alexandre’s suggestions, and the pairings were so perfect they even seemed predictable. The real earthquake came after meeting Alexandre Jean, when I got to know Sébastien Chatillon, the brilliant sommelier from Le Chateaubriand, unquestionably a genius, who broke the traditional food-wine pairing paradigm by serving champagne with a filet de boeuf. Instead of matching, there was a contrast and a powerful stimulus finally for the taste buds (and the gray matter). A healthy shock, a gymnastics. And yes, a game! Finally.”

With natural and biodynamic wine producers, she is creating a magnificent network. In her all-natural wine list, there are Alsace wines like those from André Kleinknecht, Jura wines, as well as Hungarian ones (“Robin, a sparkling white wine is the bubbles of the moment”) or Romanian ones. However, the main focus is on wines from the Maremma region in Grosseto, around Monte Amiata, with a special connection to the Gradoli boys, the producers from Lake Bolsena, which boasts a volcanic terroir only 45 minutes from Rocchette. “I decided to explore the territory, on both sides of the border between Tuscany and Lazio, thanks to the crucial help of my wine distributor Bibo Potabile, based in Arezzo, who introduced me to Massimo from Cantina Ortaccio in Latera, with wines like Confuso – a sparkling wine from an ancestral method created in collaboration with the Umbrian company Il Pulaio by Daniele Fuso. But also the talented folks from Il Vinco in Montefiascone and the extraordinary Joe Kull, a Swiss woman raised in Connecticut, who fell in love with Italy where she fulfilled her dream of becoming a winemaker by marrying a shepherd from Gradoli.” The labels of her wines are designed by the author-illustrator Jamison Odone and depict a sheep involved in a winemaking process. A metaphor of worlds coming together.

With them, Agata often organizes small events and tastings, and she even has in mind a wine microfestival. “I would like to organize round tables on hot topics like cultural appropriation (also addressed by Cook_inc. 34).” These are all characters who each deserve stories upon stories. And they have established an extraordinary liaison with Agata. Perhaps another Collectif!