Lui Ka Chun is a seasoned food journalist in Hong Kong, and the editor of one of the city’s most widely circulated (now defunct) food magazine Eat and Travel Weekly, covering wide-ranging topics from longstanding local eateries to gastro-forward travelogues.

Over the last three years, he has run a food-focused bookshop and cultivated a burgeoning community which enjoys unpacking food culture as much as cooking and eating. The bookshop, sadly, will be closing this August after the rental contract finishes, and Lui will shift gears towards his publishing venture Word by Word Collective alongside other creative and academic projects. We sat down with him on a fine spring afternoon to revisit his food writing-editing career and what Hongkongers read about food.

How did you become a food journalist?

My first job after graduating from the university was at a local newspaper. Most dailies here run a page or two on cooking and dining, and that’s how I started working in the field. I stayed there for a while before joining Eat & Travel Weekly.

Just minutes ago, someone came into the bookshop and shared that she had followed Eat and Travel Weekly from the first issue through its entire run. How would you assess the magazine’s influence over the way Hongkongers think about food?

Back then – even now, in a way – I haven’t taken much time to think about the impact of what we did. The magazine went out every week, and we kind of worked behind closed doors most of the time, trying to make our content more appealing, more in-depth and incorporate new perspectives into the stories. Instead of thinking about whether it helps the world, we were more concerned with what else could be said about Hong Kong’s food scene, and as we completed one issue after another, we realised there are so many materials to cover here that they can never be exhausted.

How did you transition from working for a magazine to establishing your own book editing business?

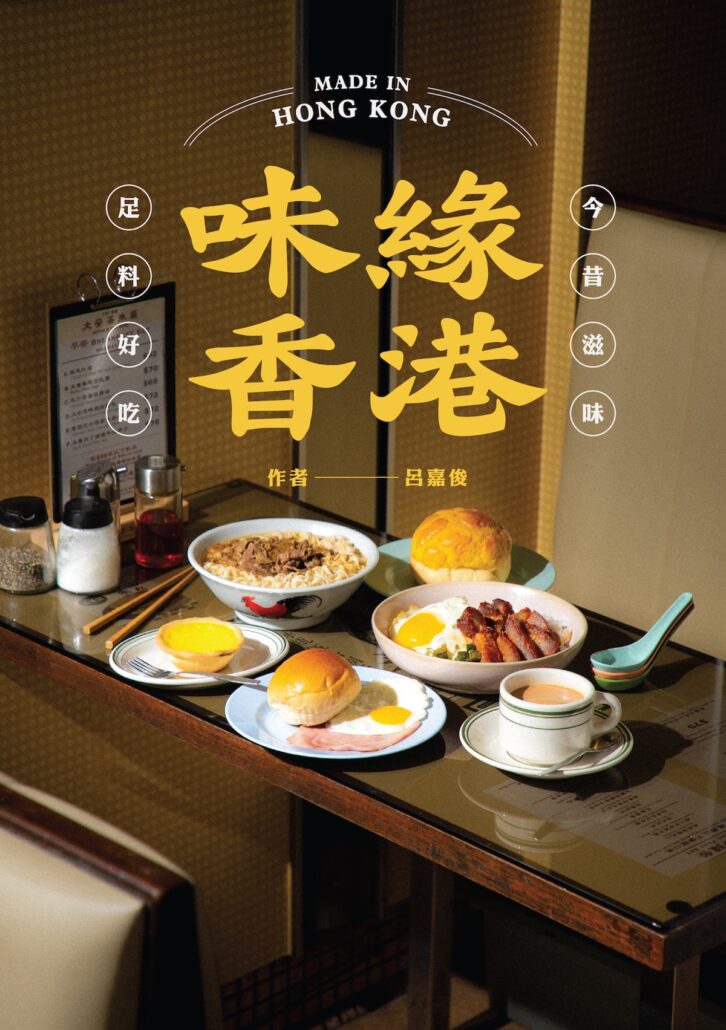

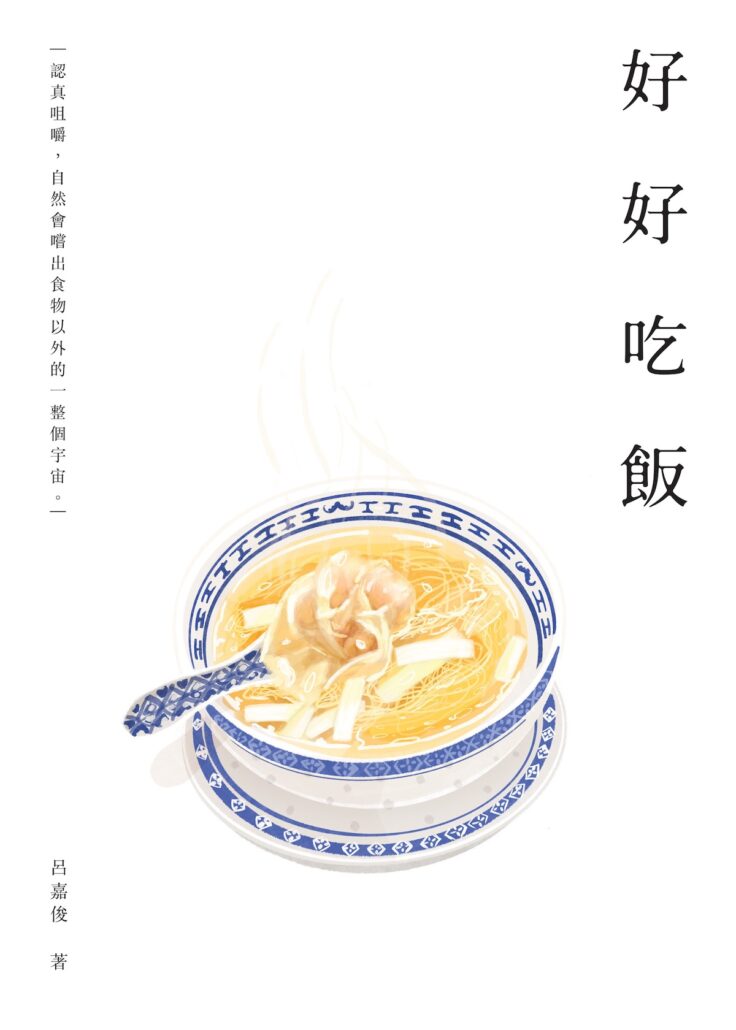

After I left Eat & Travel Weekly, I took on all kinds of freelancing projects for a while. But I also didn’t want to waste the experience I’ve accumulated after being an editor for 15 years. So, I set up Word by Word Collective just wanting to try my hands on book publishing. Many people said it was a dying industry in Hong Kong, but I’d seen enough authors out there working on book projects. That was why I gave it a try anyway, and somehow – perhaps because of my background – most of the writers who came to me wanted to publish books about food. That added to the books Eat Well and Made in Hong Kong I wrote myself, which elaborate on ideas about Hong Kong cuisine I’d been researching for more than a decade. Once they went public, I noticed how much interest there is, and that became the jumping off point for Word by Word Bookshop.

A considerable part of Eat Well and Made in Hong Kong draws from personal and collective memory about Hong Kong’s food scene and its change over the last decades. Is there a watershed moment of sorts which triggered that?

Any incident related to the society is capable of influencing how we eat. Looking back on the period between the 70s and the 90s, Hong Kong grew so fast economically that it made many aspects of our food culture disappear. People went really ostentatious with their eating habits, serving expensive shark’s fin soup with plain rice, importing everything they could find from abroad… We produced so much waste in those years, and depleted the stock of fish, lobster and other species near Hong Kong’s waters at the same time.

It seems the change came from both external circumstances and our mindset…

Yes, and I can cite a more recent example: Almost all the congee (rice porridge) shops have run out of business when in reality, congee has occupied an integral position in southern Chinese cuisine. I’d first attribute it to the low profit margin. You pay roughly 10 Hong Kong dollars for something that takes ages to cook.

But there’s not the only reason. We are in April now and already sweating without air conditioning on; Back in the days, we had a long stretch of temperate and cold weather from September to April that made hot congee a comforting dish. That period has shrunken to perhaps two months now. It’s often so warm that you won’t have any appetite for it. Finally, Hongkongers nowadays gravitate towards stronger flavours. We’re so used to MSG and mala (numbing and spicy) foods that few would appreciate the lightness of congee. As you can see, everything that happens in Hong Kong matters to the fate of a local dish. We can’t escape what’s going on around us.

Word by Word Collective has also represented Hong Kong in the Taipei International Book Exhibition for the last couple of years. Considering Taiwan has a much bigger publishing market, did your books about Hong Kong foodways garner any attention among Taiwanese readers

Certainly, and it was something unexpected. Even though we write in the same language, the writing styles in Hong Kong, Taiwan and China are completely different. Hong Kong writers, including myself, have a more “rushed” tempo. We’re almost compelled to get to the point immediately. But Taiwanese literature takes its time to bring readers into the world it’s trying to build. Their books on culinary topics are “warmer”, often driven by humanity and family. We in Hong Kong are a bit more pragmatic. So, when I got to Taiwan, I discovered the people there tried to accept Hong Kong literature and appreciate it in their own way. For me, this kind of exchange is interesting.

Hongkongers usually consume food writings through newspapers and magazines, not the best format for chewing the fat…

Possibly, columns tend to have a very limited word count and in Hong Kong newspapers, they are reserved for food criticism or something informative. Chua Lam, Kinsen Kam, Wei Ling… All the major food writers from the last generation used columns as a space for introducing intriguing restaurants or specific knowledge.

Moving on to your bookshop, do your customers come from a specific demographic?

My clientele is actually rather diverse. A part of them works in the food and beverage industry – restaurants, coffee, chocolate, bread, desserts etc. – and they tend to look for practical books, or titles that prompt them to think about food. On the other hand, I’ve got many customers who work in the arts. They think there’s a lot of common ground between art and culinary culture. And then there are architects, teachers and students. It intrigues me to see food-themed books have such a wide reach.

That’s fascinating. Do they prefer narrative food literature, recipes or coffee table books?

My impression is that readers in Hong Kong can accept many different kinds of books. “Educational” books might be slightly more popular, but no category really stands out. But I have another observation: Large books don’t do so well here, perhaps because space is so limited. No matter how beautiful it is, many customers would hesitate over an oversized book.

I saw friends and loyal readers of yours come in and give you words of encouragement, in a way lamenting its closure. Would you like to take this moment to look back on the run you’ve had?

Even though the bookshop is coming to an end, I’m at awe at the fact that it has existed at all.